The coronavirus crisis has frozen construction projects all along the Belt and Road, the century’s most ambitious geopolitical venture. Researcher Wade Shepard reports that “work has stopped along the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, Cambodia’s Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone has come to a standstill, the Payra coal power plant in Bangladesh has been delayed, and projects across Indonesia, Malaysia, and Myanmar have been stuck in holding patterns.” It was the Chinese Communist Party that caused this problem in the first place, and now it might appear that the Party is suffering the economic consequences. But the truth is that a significant number of Belt and Road projects had stalled long before the current crisis. The coronavirus shutdown will just emphasise a pattern that has been in evidence for some time now, and in this sense it will hardly inconvenience China’s authorities.

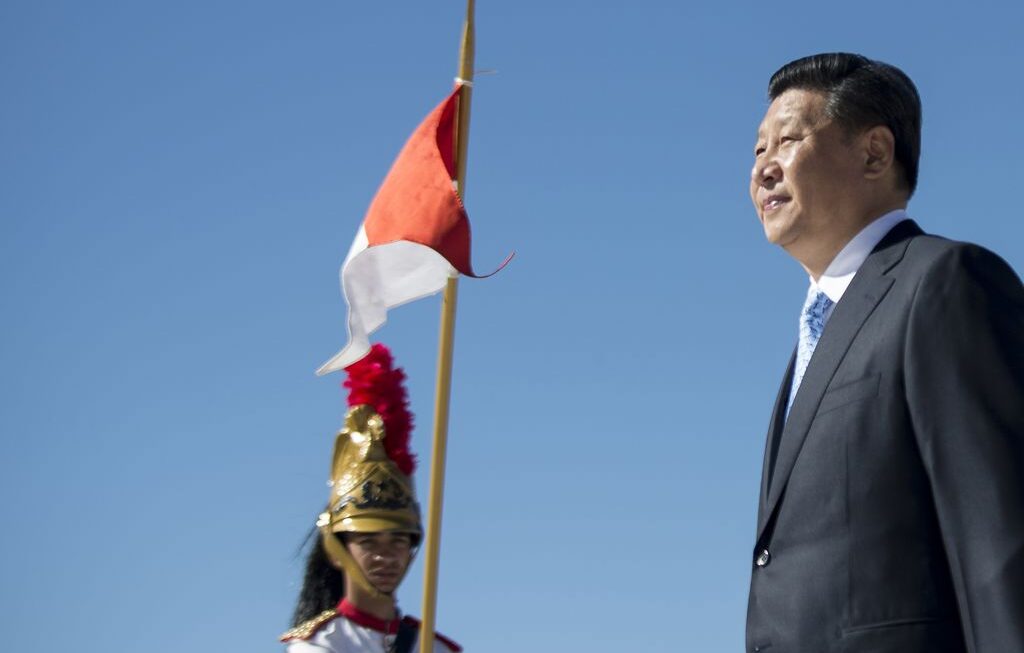

The Belt and Road was first unveiled by Xi Jinping in 2013, and its ambitions were vast. The stated aim was the forging of deeper connections with much of the rest of the world – Eurasia, Africa, South America, Oceania. The titular ‘Belt’ referred to the project’s land route, taking the ancient Silk Road as inspiration (‘The Silk Road Economic Belt’), while the ‘Road’ referred, somewhat confusingly, to the sea (‘The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road’). The Communist Party had its eye on shipping lanes running from the hotly-disputed South China Sea down through the Malacca Strait towards Australia, and westward from the Bay of Bengal to the Persian Gulf and beyond.

For the past seven years the CCP has been planning ports and pipelines; investing in factories, roads, railways, power grids. 138 countries are now involved – a combined GDP of $29 trillion dollars, and an area containing about 4.6 billion people. The Belt and Road has become impossible to ignore. So far, the Communist Party has been presenting the project to us with smiles and flowers and ingratiating smiles – we are told that China wants to “deepen political trust; enhance cultural exchanges; encourage different civilisations to learn from each other and flourish together; and promote mutual understanding, peace, and friendship among people of all countries.”[1] This, we are told, is “win-winism.”[2]

The view from the ground does not match the grand imagery of the publicity drive, however. Those who have been to investigate have found a surprising lack of activity, even prior to the coronavirus outbreak. “Melaka Gateway is currently a barren slab of reclaimed land lingering off the coast of Malaysia, polluting the local ecosystem,” said Wade Shepard in his report on the ‘struggles’ of the New Silk Road. “The $10 billion Sino-Oman Industrial City is an 11-square-kilometer expanse of fenced-in empty desert.”

More of the same can be seen at Gwadar, Pakistan’s much-hyped coastal site. Gwadar was promised $230 million, with factories, roads, a seaport, and an airport all scheduled for completion by 2016. Four years on, there is little sign of any of this development, according to Sheridan Prasso and Jeremy C. F. Lin at Bloomberg. “The site of the new airport… is a fenced-off area of scrub and dun-coloured sand… The factories have yet to materialize on a stretch of beach along the bay south of the airport. And traffic at Gwadar’s tiny, three-berth port is sparse… An expressway connecting the new airport to Gwadar was supposed to have been completed by CCCC [China Communications Construction Co.] in 2018… In October [2019], dump trucks with piles of rocks were parked on the edge of the existing roadway nearby, but no work was being done.”

There will be many more of these sites: failed, postponed, or downsized projects stretching across Asia and Africa. “We still haven’t really discovered how many white elephants are roaming along the Belt and Road from those earlier years,” says Jonathan Hillman of Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies. The Chinese authorities, normally so uncompromising, have been cancelling with a minimum of fuss at the first sign of a hitch. When crowds of Kyrgyzs protested the creation of a $275 million free-trade zone on the Kyrgyzs-Chinese border, the Party quietly pulled the plug on the project.

The flow of money is drying up fast – so fast that it almost seems as though the CCP has lost interest. China’s overseas investment growth peaked at 49.3% year-on-year growth in 2016, and then fell by 23% in 2017, and another 13.6% in 2018. In the first six months of 2019, Chinese foreign direct investment rose by just 0.1%. Li Ruogu, former president of China’s Export-Import Bank, actually admitted publicly in 2018 that most countries involved with the Belt and Road have no chance of being able to afford to pay for their projects.

So does this mean that Xi Jinping’s dream is a monumental failure – a herd of white elephants scattered across the globe? Could China’s authorities really have been that short-sighted? Unlikely. Belt and Road funding is centred around loans, not grants, and with good reason. Djibouti’s public external debt has increased from 50% to 85% since signing up for the Belt and Road, and almost all of it is now owed to the Export-Import Bank of China.[3] Pakistan, one of China’s chief partners, will owe $5 billion by 2022.[4] If the money is not paid back in time, the Chinese authorities will take charge of power plants, coal mines, and oil pipelines throughout the country. They will also enjoy leverage over the Pakistani government.

Some states have sensed the way things are headed. Fearing bankruptcy and “a new version of colonialism,” the Malaysian government actually pledged at one point to cancel its Belt and Road projects. In the end the authorities went back on their promise, resurrecting a $10.7 billion rail link. They will come to regret this failure of nerve. States should get out as fast as they can. Before long the debt traps will be springing all along the Eurasian littoral to the Horn of Africa.

The Communist Party never had any real interest in global connectivity, according to Nadège Rolland, senior fellow at Washington’s National Bureau of Asian Research. Long-term investment was not part of the plan. Indeed, the Party has probably been hoping that Belt and Road building projects fail as frequently as possible. Those that turn out to be genuinely workable can be delayed and renegotiated ad infinitum. The true goals were always political rather than economic. China’s spreading influence among Belt and Road nations will enable the CCP to speak with many more voices in an international arena like the United Nations. Beijing is also likely to exert increasing control over natural resources throughout Belt and Road regions.

But there is another, more urgent concern. The debt traps have been strategic. China’s authorities conjured a key port from nowhere by pumping money into what was formerly a small shipping town on the Sri Lankan coast. When the debt became unmanageable, the Party agreed to write it down in exchange for century-long control of the port. (So much for all that talk of “mutual understanding, peace, and friendship.” As Brigadier General and China expert Robert Spalding points out, these are the actions of a loan shark, not a benevolent ally.[5]) Within months, a Sri Lankan naval unit was established at the site, and then a Chinese frigate was offered to Sri Lanka’s navy. Such offers will open the door for a steady stream of Chinese training and support teams, and soon enough this navy will be ‘Sri Lankan’ in name only.[6]

The port in question (at Hambantota) was chosen for its location, taking its place as one of the so-called ‘String of Pearls’ now hanging around the neck of the Indian subcontinent. These pearls are ports, bases, and infrastructure projects that will ultimately allow the CCP to project power across the Indian Ocean, and to check the rising power of India itself. Indeed, the Pakistani port at Gwadar made little sense from a purely economic perspective: there were better connected ports already in existence. But Gwadar fits perfectly into the String of Pearls.

And so beneath the brightly-coloured official narrative – all hand-in-hand globalisation and cultural flourishing – we find the brute reality of militarisation. The Belt and Road’s China-Pakistan Economic Corridor involves an agreement by which Pakistan’s Air Force will build JF-17 fighter jets for the People’s Liberation Army, the military wing of the Chinese Communist Party. When Xi Jinping visited Myanmar in January 2020 to sign infrastructure deals for a deep water port at Kyaukphyu, he also made sure to hold talks with the nation’s armed forces chief, Min Aung Hlaing. And after constructing both a port and an overseas military base at Doraleh in Djibouti, the CCP convinced Djibouti’s government to seize control of a nearby container terminal operated by DP World, terminating the Dubai-based company’s lease and effectively ensuring that both of Djibouti’s two major ports were now under Chinese control. Small wonder certain Indian scholars have spoken of “the silk glove for China’s iron fist.”

The Belt and Road was also set up with the aim of gathering big data. A twenty-four-hour surveillance system has been planned for Pakistan’s cities – all the way from Peshawar down to Karachi. The Zimbabwean government has given the green light for the Chinese company CloudWalk Technology to begin a nationwide facial recognition program. Smart security is coming to Zimbabwe’s airports, train stations, and bus stations, a smart financial service network is being built, and all the collected information will fall straight into the lap of the Chinese Communist Party. Zimbabwe is not alone. In fact, Huawei’s ‘Smart City’ concept was already active in 40 different countries by 2017.

Former US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson sees Belt and Road agreements as Faustian pacts; deals with the devil. Seduced by the lure of the renminbi, states are selling their independence.[7] The governments that are now signing up should have learned the lessons of the past – African countries, for instance, did not benefit in the slightest from two decades of Chinese investment prior to the Belt and Road. Local firms were simply displaced. Now the same story is being repeated on a much larger scale. At its most extreme, this process can resemble colonialism. The Cambodian port city of Sihanoukville, for instance, looks more and more like a Chinese outpost. More than 90% of its businesses are now Chinese-owned, and the city even has a new cod-colonial name – Xigang. “Native residents have been more or less relegated to the lower rung of the city’s service economy,” says the journalist Chris Horton. They are employed “as tuk-tuk drivers, parking attendants, and restaurant and hotel staff.”

Temporary shutdowns will make no change to the Communist Party’s Belt and Road masterplan. However, there may be hope in people power. We have already felt the rumblings of discontent, especially in South East Asia, but it’s not enough for projects to simply be cancelled or suspended, as after the Kyrgyzs protests. Public anger needs to be directed at the Communist Party and its insidious influence, rather than the construction of particular dams and factories and airports. If citizens all over the world were to adopt the rallying cry ‘No Belt And Road’; if they were to give their governments the clear message that they want to opt out permanently, then these countries may yet stand a chance of preserving their sovereignty.

Notes

[1] Bruno Maçães – Belt and Road: A Chinese World Order (C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., London, 2018), p42

[2] Clive Hamilton – Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia (Hardie Grant Books, London, 2018), p126. Hamilton cites “China offers wisdom in global governance,” Xinhuanet, 6 October 2017

[3] Maçães, op. cit., p46

[4] Ibid.

[5] Robert Spalding – Stealth War: How China Took Over While America’s Elite Slept (Portfolio / Penguin, U.S., 2019), p75

[6] Maçães, op. cit., pp. 46-7

[7] Ibid., p11

Brilliant article. I found this website and your writing through your recent article in Quillette. I will be sharing it with friends.

Thank you!